Created for and delivered to first year undergraduates on the Bachelor of Arts and Sciences programme at University College, run by Carl Gombrich. If you wish to use or reproduce please contact me first.

Slides here

Audio:

Created for and delivered to first year undergraduates on the Bachelor of Arts and Sciences programme at University College, run by Carl Gombrich. If you wish to use or reproduce please contact me first.

Slides here

Audio:

The full slides, script, and recording for presentation given at Science In Public and 4S/EASST. Please do not use without contacting me first.

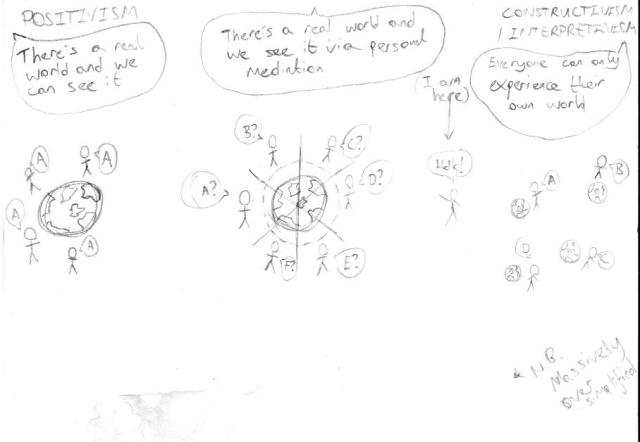

The language of social sciences has a problem with right levels of drama. We reserve the driest of terminology – ‘positivism’, ‘constructivism’, ‘relativism’ – for describing some pretty fundamental human processes of making sense of the world. We then describe differences between these labels as ‘struggles’, ‘competitions’, or even ‘conflicts’, all of which suggests two large well-opposed sides confident in their preparations and even more confident in their beliefs. It does not suggest an image of me surrounded by dirtied coffee cups and PhD data printouts upon which I have scrawled ‘I want to believe something but I don’t know how’.

The point I want to make today is this. That which social sciences call ‘methodology’ are, at heart, tied to some deeply personal factors. If you’ve never heard of methodology, it’s the intellectual process of justifying why you did certain things during research. If you have heard of methodology, you’ve probably been taught about it as communal process, with a researcher becoming encultured into one (or, though more rarely, more than one) of multiple schools of thought. All schools agree that trying to understand humans and society is quite a complicated task – I’m sure there are people who think that humans and society can be explained using straightforward rules, but I will suggest that these people probably haven’t done much social science (or, indeed, interacted with many humans). But one of the key issues underlying differences between schools is the following question: how do researchers stand in relation to ‘the real world’? To illustrate that, have a picture I did at a Drink & Draw meet:

(Meanwhile the person to my left was doing an ink portrait of – I eventually realised – me, and the person to my right was producing a vivid sketch of the Yorkshire Moor. I’m not a regular.)

As an example of the above, take the question ‘is country A happier than country B?’. It’s not a straightforward one, but one way to approach it might be to compare suicide rates. That way, you can (partly) represent the complicated and personal phenomenon of unhappiness as a series of numbers which everyone can agree on. Not so, say others. Even the seemingly objective ‘rate’ is actually the product of various social processes. Different countries/coroners may record suicide rates differently.Ok, say the positivists, but in that case how do you give any answer to the original question beyond ‘unhappiness is complicated and personal?’. More importantly, how do you give any answer which has any form of reliability (assurance that different parties will agree on the same answer) or validity (assurance that the answer does in some way match up to the world)? Ultimately, how to ensure different researchers can’t just give entirely different answers to the same question, thus reducing so-called ‘answers’ to personal opinion?

That’s a *heavily* summarised social science 101. My argument here is that these questions go beyond the intellectual and into the rather personal. To again raise the point of language, we tend– ‘naïve positivism’, ‘anecdotalism’, and suchlike. Based on my position on that spectrum, the slur that wounds me is anecdotalism – the claim that if you’re going to allow researchers to just give idiosyncratic, rather than standardised, views then all findings are basically just personal stories. (This criticism often appears as the phrase ‘the plural of anecdote is not data’). I feel this is an argument which is strong on dismissive language and weak on clarity. If I was to tell you the anecdote ‘hey so I was in my lab the other day, and I was doing this stuff, and this thing happened which I thought was interesting so I did the same stuff a few more times and, y’know what, the same darn thing kept happening’ then I’m basically reporting an experiment in a rather informal way. Less facetiously, all research comes ultimately from people encountering stuff and relating it to other people and the label of ‘anecdote’ does no work in distinguishing how different fields actually do research in practice. Instead, it’s used to dismiss a stereotyped or idealised view of some research that’s different to yours.

On the flipside of this quite negative view, ‘ideals’ also play a positive role in giving things to aim at; for example, many positivists might accept that 100% validity and reliability is unachievable but nonetheless worth trying for. But a problem I have as a constructivist is that it’s not easy to reject ideas like ‘validity’ or ‘reliability’ when it’s hard to find words which bolster an opposite position – apart from ‘invalid’ or ‘unreliable’, and those labels don’t do wonders for one’s confidence. And confidence is important in all this. That earlier diagrammed question can be more brutally phrased as ‘what’s the point of the researcher?’. What’s the point of all our training, lengthy and sometimes painful and often publicly funded?[5] For those towards the positivist end, this teaches a researcher how to recognise and extract relevant information from the world and to submit these in the ‘correct’ way for peer scrutiny – in other words, they learn how to show validity and reliability. But if you don’t believe in validity or reliability or some ultimate ‘correct’ answer, then what are you learning to do? Are you learning pragmatic skills of how to find and report interesting information, thus making academia a quite extreme and laborious version of long-form journalism? Or are you learning how to present your individual take on the world in a way which makes colleagues go ‘that’s interesting, ergo you are interesting’ – making research a form of what is often called ‘modern art’, where a small group stand around exclaiming ‘what a clever work, let me now explain why it’s clever in a way which shows you that I too am clever’ while a larger group claims ‘my five-year old could have done that’ and a much larger group simply neither know nor care about it at all.

I’m still not confident on the answer to that. But look closely at the above paragraph – I’m talking about researchers, long-form journalists, and modern artists in exactly the same idealising and dismissive way as I’ve argued positivists talk about constructivists. I’m actually not intending to dismiss long-form journalists; my point is that they do their work without the hefty training seemingly required by academics, so why can’t academics? I am being dismissive of the modern art community, while being conscious that my description is of a stereotype rather than first-hand experience (and also a stereotype that I am actually worryingly adept at slipping into). The point is this. My idealised image of the long-form journalist is of someone who presents their reader with a clear, convincing, and detailed picture of a world, while at no point suggesting this is the only or best picture of that world. This is a description I would be happy to align myself with. By contrast my idealised image of the positivist researcher is of someone who wants everyone to see the world (or a portion of it) in the same way as them. I feel this to be a bit simplistic and (potentially) morally problematic. And my idealised image of the modern art practitioner is of someone more interested in promoting their own personal brand than in actually welcoming input from the wider world, or at any point asking ‘is this possibly just a bit stupid’.[7] And all that goes a long way to explaining where I place myself on the above spectrum. That’s not to say I wish positivists and modern artists didn’t exist, or that I automatically dislike their contributions, or that I don’t want to talk to them. I just don’t want to be one of them.

None of that will appear in my PhD methodology chapter. None of it would be accepted intellectually. I think that’s a shame. Because, setting aside differences between methodological schools, my ideal of academia is of a community that understands the implications of language, avoids uninformed dismissal, and welcomes full honesty and candour. And whether or not you agree with that, any academic’s methodology has to proceed from the belief (even hope) that some world, or some portion of it, can be understood somehow. Otherwise we’re a bit pointless. And that is deeply personal.

(The title, fyi, is a reference to an old metaphor about methodologies being ‘lenses’ one can take on and off to see differently. I suggest it’s not as easy as that)

[1] This example is based on my (secondhand) knowledge of debates around Emile Durkheim’s book Suicide. There’s also an example about vote counting involving some social decisions about what counts as a spoiled ballot, but I’m struggling to find the ref for that. Send help.

[2] Somewhat ironically I feel, or at least rather annoyingly – see my previous thoughts on clear language

[3] Or alternatively, in a 17th century way when experimental method was becoming a Big Thing. A lab scientist might respond with the point that experimental results are corroborated by replication from other parties, so they’re not so much personal anecdotes as shared stories. Fine in theory, but in practice that doesn’t really happen.

[4] I’m sure the same is probably true of ‘naïve positivism’, for the record.

[5] Apart from, y’know, providing universities with a pool of cheap teaching labour and seminar organisers. (This is, somewhat ironically given the main body of this post, a very dismissive way of describing quite a multifaceted problem).

[6] I.e. in the stereotypical sense of art that comes across as more weird and pretentious and of questionable aesthetic value Apologies to any real, rather than stereotyped, modern artists. One could also think of niche music groups, fashionistas, or any of the people brilliantly, if often disturbingly, satirised in Charlie Brooker and Chris Morris’ Nathan Barley.

[7] Again, I refer you to Brooker and Morris (ibid.)

I had the wonderful experience of being on the panel for the pilot recording of a new science-ish (emphasis on the ish) comedy podcast ‘Never Explain’. Future recordings and ticket details here https://scienceshowoff.wordpress.com/2016/04/15/never-explain-podcast-panel-show-recordings-in-may/ .

Was a lot of fun, highly recommended.

Draft of a review I did. May be of interest to those who like popular astronomy, history of popular astronomy, semicolons, and/or bizarrely long sentences. Final version, along with other reviews by some excellent and lovely people, here (behind paywall) – http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayJournal?jid=BJH (December 2015, Vol. 48, Issue 4).

In this book Sir Francis Graham-Smith, former Astronomer Royal and Vice-President of the Royal Society, speaks from over seven decades of personal involvement to describe the rise of radio astronomy “from the first discovery of cosmic radio waves to its present role as a major part of modern astronomy” (p.vi). The expansive subject matter is organised by chapters centred on objects, from natural objects such as pulsars or black holes to the technical objects – dishes, arrays, and so forth – associated with their discovery. This is a technique familiar in popular physics books, from Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time (1988) to Michio Kaku’s Hyperspace (1994). At its best this structure allows neat linkage between some key ingredients of popular science writing: specific details of objects become part of engaging discovery narratives, and then are connected to the rest of the universe through broader physical theories. However, in this work all the experimental narratives, technological developments, biographies, astrophysical crash-courses, and often over-specific details arrive and supersede one another at an alarming rate. The cumulative effect energetically conveys the breadth and activity of radio astronomy, but does little to aid understanding.

The problem seems to stem from a lack of clarity over audience. This is most notable in the inconsistent levels of basic familiarity expected of readers. The basics of the electromagnetic spectrum are given as much space as spherical harmonics and Fourier analysis; familiar descriptions of Newtonian and Einsteinian gravity rub shoulders with graphs and figures lifted, with little elaboration, from more technical spheres; and terms like ‘azimuth’ and ‘arcsecond’, the bread-and-butter of the field, are brought in without definition. But this scattergun approach is perhaps more problematic in the level of detail readers are expected to engage with. An extremely large number of astronomical objects, technologies, techniques, characters, and developments are introduced throughout the book. Some are introduced in great detail, arguably too much detail – a whole page on the emission spectrum of carbon monoxide, for instance (pp.76-78). Others are passed over with frustrating scantiness; in particular, Graham-Smith has a habit of omitting dates from many of his historical accounts. Of all these details, some disappear quickly while others reappear unexpectedly in the midst of fresh new information; to give just one example, the story of Karl Jansky’s radio emitters features in a discussion of telescopes on p.15, but is then brought back on p.71 in a discussion of synchrotron radiation. Such connections between stories and objects are interesting, but there are simply too many to make this a casual read. The risk of overwhelming the reader is compounded by intermittent signposting, in particular the lack of real introduction or conclusion to any of the chapters. The net result feels like reading a peculiarly themed build-your-own-adventure story from cover to cover, rather than following any of the singular plot paths offered.

This is a shame, because many of these narratives are of great interest in their own right. Some, such as the formation of cosmology as an observational discipline, have been told in more detail elsewhere (in particular in the work of Helge Kragh). However, others are greatly enhanced by the personal narration of Graham-Smith. Anecdotal mentions only appear infrequently, but still serve to convey the unpredictability and excitement which clearly permeated the field. His description of the tracking of Cygnus A by observatories in Cambridge, Jodrell Bank, and Australia –“the moment when radio astronomy showed its potential in observational cosmology” – points to a time of continual trying-and-finding, and shows the importance of multi-location collaboration while subtly hinting at the drive of competition (pp.85-90). Equally, many interesting segments arise from the author’s expertise in the factors which set radio astronomy apart from other techniques of astronomical surveillance. In particular, there are fascinating technical challenges around the size required of the apertures, leading to the international development of kilometre-sized connected arrays (pp.187-223). These could, if arranged more clearly, prove excellent grist to an internalist historian’s mill.

But these criticisms are perhaps unfair given this is a work intended as popular physics – which brings us back to the problem of audience. In a work of this subject matter, it is perhaps difficult to know whether readers are looking for personal stories to flesh out the physics bones, or for a focussed account of a particular scientific field. But in order to include all those narratives, this book would have benefitted from an alternative format – perhaps some way of distinguishing discussions of natural and technical objects, or separating different levels of detail, or a way of visually tracing the recurrent stories. As it is, I suspect only a select proportion of readers could really engage with all the material; personally speaking, even degree-level physics knowledge was not sufficient equipment. If the only reader who could mentally catalogue the oncoming stream of information would be an already astronomy-literate one looking to broaden their knowledge, then we must ask the question of what the book adds over a series of Wikipedia searches. One answer to this question is the charming glimpses into Graham-Smith’s personal enthusiasm. But in this case enthusiasm needs to be balanced with control of the subject matter, tighter editing, and much greater awareness of the recipient. It is a cliché that too much expertise can inhibit the ability to teach, but this work seems to be a case in point.

-Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes, Bantam Books, 1988

– Michio Kaku, Hyperspace A Scientific Odyssey Through Parallel Universes, Time Warps, and the 10th Dimension, Oxford University Press, 1994

A talk I gave at the Oxford Internet Institute . Thanks to Vili Lehdonvirta for organising, and all the (physical and digital) attendees.

Update: At the invitation of Vyacheslav Polonski I went back to OII and delivered a second version – similar to above, but with fewer details and some speculative thoughts which have occurred to me following the previous incarnation. Recording available here.

For anyone who’d rather read a (similar but somewhat different) written version than listen to my voice for 40min (for which I don’t blame you) – https://sidewayslookatscience.wordpress.com/2014/02/02/in-praise-of-shortenificization-a-review-and-a-rant/

Slides here OII Presentation . Please ask if you wish to reproduce in whole or in part.

Delivered at the Royal Institution, London, 14th November 2015. With thanks to Hattie Lloyd for the invitation. More details on the Society for the History of Alchemy and Chemistry here.

Slides available here, and half-finished script here. Please contact me if you wish to reproduce any of the material.

As mentioned in the talk, for much of the material I am grateful to Dr Emily Dawson.

I helped out with another episode of the Global Lab podcast series. We talk about digital politics, 18th century patronage, and rhinos. It’s all good fun.

The Presentation (including big list of useful resources at the end):

SiP Presentation

A Useful Bibiliography

Internet Research Bibliography

A Fun Crowd-Sourced Mock-Up Spreadsheet

Mockup IFLS

More on my research project and questions (though a little old now) https://sidewayslookatscience.wordpress.com/2014/10/16/one-year-in-research-part-i-giving-birth-to-a-research-project/

A talk I gave at the Oxford Internet Institute . Thanks to Vili Lehdonvirta for organising, and all the (physical and digital) attendees.

Update: At the invitation of Vyacheslav Polonski I went back to OII and delivered a second version – similar to above, but with fewer details and some speculative thoughts which have occurred to me following the previous incarnation. Recording available here.

For anyone who’d rather read a (similar but somewhat different) written version than listen to my voice for 40min (for which I don’t blame you) – the unifinished script is here OII Talk and the blog that started all this off is here https://sidewayslookatscience.wordpress.com/2014/02/02/in-praise-of-shortenificization-a-review-and-a-rant/

Slides here OII Presentation . Please ask if you wish to reproduce in whole or in part.